THOUGHTS OF A LIVING WORK OF ART

Obviously all art is conceptual in one sense or another, so what is distinctive about the conceptual art movement which began in the early twentieth century?

Modernism as a general socio-cultural phenomenon is a highly reactionary movement, emotionally driven to reject the values and styles of western civilisation rather than evolving beyond them. Undisguised pleasure in shocking those who identify with the traditional canon is an important part of the modern spirit.

In the early days of this movement, breakthroughs in scientific understanding, in new technology and in the use of new materials, were like a breath of fresh air to a generation who were living in a world largely undisturbed by major wars and changes in political regimes. Traditional sources of information and meaning were disrupted by the huge increase in the speed of electronic information processing and the First World War resulted in major transformations of the social structures. At the same time developments in psychology, sociology and physics were undermining both religious and enlightenment world views.

Changes in perception had first appeared in the arts during the Nineteenth Century, however in the early Twentieth Century the place of artistic creativity as a socio-cultural phenomenon was questioned. What was the meaning of a work of art?

Who decided what constituted a work of art and what did not? Were there any objective criteria?

This early form of post modernism raised the question of the objectivity not only of perception but of values.

The Romantic Movement emphasised the interaction of the artist with the natural and spiritual environment. Sincerity and passion in painting became more important than accurate representation or dramatic narrative. In architecture and design the Gothic Revival and the Arts and Crafts movement went back to the medieval period for inspiration to emphasise the social function of art rather than its function as a statement of status for wealthy patrons.

I share the extremely passionate opinions of John Ruskin on the degradation of creative inspiration and the soul of man that followed the Renaissance and Wyndham Lewis creative outbursts at similar degradation during the 20th Century.

Conceptual art is a thoroughly Twentieth Century phenomenon, being closely linked with the prominent place that political ideology has held. Like the Romantics of an earlier generation, artists saw themselves as rebels against the increasing numbers of self-satisfied middle classes. However, unlike most of the Romantics, their rebellion was not driven by a consuming passion for experience but by ambivalent identification with the rising secular ideology of

egalitarianism.

Socialism as a value system is a form of pseudo-scientific Social Darwinism which regards all past societies as morally inferior to a coming utopia based on a powerful secular state which will eliminate all racial, economic and sexual discrimination. Reductionism and materialism taken as absolute values in science proved highly successful in controlling the material world but have had a catastrophic effect on such vital spiritual values as learned discrimination,

love, play and transcendental aspiration.

Like Romantic art, conceptual art makes its impact by provoking feelings rather than by impressing people through skill in composition and craftsmanship.

The value of such art lies almost entirely in its originality, relevance and profundity of perception. Only an emotionally immature individual would be satisfied merely to shock.

Judged by such criteria the radical first phase of conceptual art, which took place a hundred years ago, was successful. Art galleries were shown to be little more than museums and their boards of directors had replaced the aristocracy as the elite who largely monopolised ownership and determined the meaning and value of works of art. Works of art had become investment commodities and their cash value could be manipulated like the diamond market.

Conceptual artists such as Duchamp first demonstrated through his ‘readymades’ that anything exhibited in an art gallery was ipso facto a bona fide work of art. Later, Manzoni and others demonstrated that anything produced by anyone calling themselves an artist, even their own excrement, could become a work of art if exhibited as such and auto-erotic narcissists received government grants for displaying themselves in galleries, frequently self mutilated, as ‘living statues’.

Apart from resentment based egalitarianism, cash value is the only absolute value in a civilisation where the competing materialistic ideologies of capitalism and socialism have almost completely destroyed other value systems.

The combination of secular state authorities spending other peoples’ money, together with the mass media owners and the art critics employed by them, played a large part in creating the cash value of art works and the acceptability of those creations many of were neither very original nor very profound.

Successful rebels usually turn out to be more authoritarian and opposed to change than traditional elites and in conceptual art this is particularly true.

Installations in art galleries rarely provoke any profound conceptual challenges. Disgust or bitter mirth is a common public reaction amongst those who are not experts in the impenetrable jargon of the artists and art critics.

Boredom is another reaction when presented with a politically correct ‘statement’ about oppression and discrimination etc.

A NEW DIRECTION

It was against this background in the late 1960s that I decided to take conceptual art a step further than the pioneers had contemplated. The Living Work of Art project is not just another living statue, where the visual-tactile body is an object transformed by clothing, tattoos or paint, but a psychological, social and cultural transformation of a living human being, as a

being and not an object, into an artistic creation.

I saw a key concept in the tradition of the alchemical Androgyne, where a sexual, psychological and spiritual relationship between and man and woman helps to develop male aspects of the woman and female aspects of the man which otherwise take the form of what Jung called shadow personas, the animus in women and the anima in men. Widespread changes in women’s roles and

birth control pills were making this ideal more achievable.

What is commonly regarded as human nature is frequently subject to cultural change. Agricultural societies transformed the previous hunter-gatherer male-female bond. Fertility became an overriding value, and men valued their identity as land owners, fathers, warriors and providers. This continued in the early stages of the industrial revolution. Eventually the extended family in the countryside was replaced by the nuclear family in the town.

As the industrial society developed and institutions for educating children multiplied married women began to enter the work force alongside the men. From the Enlightenment onwards women began to question the very idea of patriarchy.

They wanted to avoid being regarded as sex objects for men’s gratification, providers of offspring for male immortality longings or having to act as ‘mother-goddesses of the home’ to men who still needed a woman to adore and base their lives around.

I come from two generations of feminist mothers whose choice of their mates was romantic and who prized their independence. I wanted to remain free from “the realm of necessity” and to be prized for my “being” rather than for my usefulness in fertilising a woman and providing economic support for her. I decided that the solution was to become a work of art in a romantic relationship in which the woman was not only free from economic dependence on the man but actually supported him.

In this way the woman’s animus persona of material and social independence could be developed at the same time as the man’s anima persona of emotional independence from needing approval.

My double honours degree in psychology and sociology caused me to focus on the psychological motivation for social behaviour and I was persuaded, like Freud, that there are important mythological motivations which are largely unconscious. Like most anthropologists I do not accept Freud’s belief in the universality of the Oedipus complex, nor do I think that he interpreted it correctly. It would be better called the Jocasta complex as she is the prime mover throughout, whereas Oedipus reacts like an immature child. In the non-patriarchal hunter-gather cultures the relationship between mother and son is seen as potentially dangerous and young males undergo a series of extensive rituals of weaning carried out away from the women.

It could be said that the mythological motivations of males in these cultures are based on what I call the “Orestes Complex” in which the male is pressurised into killing his mother-figure in order to become a mature man. Hunter-gatherer men are more concerned with “being” rather than “doing”, and like male animals spend a lot of time in display to impress the women. They appear close to being living works of art.

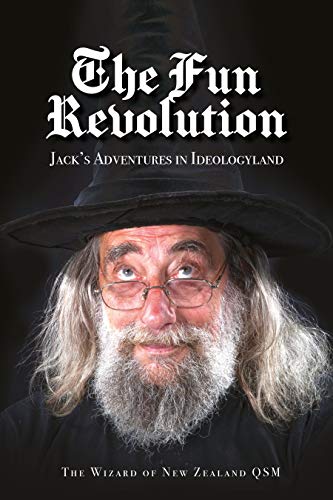

My appointment in 1969 as official Wizard of the University of NSW jointly by the University Administration and Student Union, and my later appointment by the Union of Melbourne University as Shaman, Cosmologer and Living Work of Art, provided me with the essential roles I needed. I exhibited myself in the manner of a hunter-gatherer male hoping that young independent women of feminist views would be attracted. I was not looking for a mother-figure or a sister-figure. I wanted a romantic woman whom I could “acculturate”. I was not emotionally opposed to polygamy but I was emotionally opposed to serial monogamy.

As a “master” and not a “slave”, I made a commitment to those women who formed a relationship with me that I would not leave them but that they could leave me without a fuss if they found the going too difficult. After some years of disappointment a suitable young woman volunteered and has been my “inamorata” ever since. She became my curator when, in 1972, the director of National Gallery of Victoria accepted the offered donation of my living body made by the World University Service of Australasia. The Living Work of Art was thereby authenticated but obviously could not become part of the permanent collection. I was on “extended loan”.

Karl Marx was most emphatic that our consciousness is determined by our socio-economic relationships. I had already crafted my new identity most carefully by ceasing to renew any secular state documents defining my roles and living for a short time in 1969 on a small honorarium paid jointly from the university and student administrations. I would only accept official identification as The Wizard and this took many years of creative evasion of the

five-yearly census in New Zealand until I finally obtained a passport made out to The Wizard of NZ. During this time when my whole role complex had been modified in a creative playful direction I began to experience major shifts in my consciousness. Diverse material I had been absorbing for years began to come together in meaningful patterns. I cannot describe the ecstasy that I experienced at this time.

THE UNIVERSE AS A CONCEPTUAL ART WORK

Both the microcosm of the androgyne and the macrocosm of the universe needed to be conceived in an original creative way. The living work of art needed a frame. The two developed together and I began to put together a synthesis of magic, religion and science in an aesthetic form, which I published in 1973 as the Post Modern Cosmology.

Conceptually separating intention or dynamics from extension or kinematics, I linked the two through experiential eventuality or history. The only approach similar to my own that I have come across since I began, is the “process philosophy” of the philosopher and mathematician, A.N.Whitehead. He demonstrates that the only truly real thing in the universe is an experienced event. Time and spacial location are abstractions which, although useful concepts in the technological manipulation of materials, are often mistaken as existing in concrete form. Whitehead was inspired by both literary Romanticism and Platonic religion.

I also found Tiehard de Chardin’s synthetic religious-scientific cosmology helpful, particularly the concept of “involution” as the corresponding increasing complexity of dynamic intention that accompanies evolution. Ilya Prigogine’s transformation of thermodynamics into an evolving process and Erich Jantsch’s theories of self-organising systems based on this, were essential in

specifying the evolving kinematics. I did my best to include the latest theories in other branches of scientific knowledge including biology, ethology, psychology, sociology, and anthropology in my “grand theory of everything”.

SENSATIONALISM

There was a major problem. How on earth could I expect anyone to be interested in such a complex set of ideas by what appeared to be an eccentric artistic exhibitionist? A sensational gesture was needed!

The sociologist Pitirim Sorokin, following in the tradition of Joachim of Floris, Giambattista Vico, and Karl Marx, had proposed a theory that civilisations went through a series of stages. First a creative spiritual period the “ideate” stage, then a period when the ideas were implemented in structural forms, the “ideational” stage, and finally the “sensate”

stage, when the ideas were largely forgotten and the structures themselves became idolised. Finally the civilisation collapsed or was reborn through the emergence of new ideate stage. During the construction of my cosmological synthesis, which I regard as an “ideate” cultural phenomenon, I had hypothesised a period following the sensate stage which I termed the “sensational” stage. The post industrial shift from production to consumption, the growth of advertising to create needs and political ideologies idolising the secular state seemed to me to be qualitative changes transforming the previous sensate industrial culture.

As well as commodity advertising which was all pervasive, sensationalism dominated the news and entertainment media and saw the rise of a new aristocracy of celebrities. I had made use of what I called “harmless sensationalism” , the Fun Revolution, at the University of NSW as a technique to prevent student violence and to get reforms.

In 1973 I came across the answer. For a truly sensational dramatic effect I turned the world inside-out by making a conformal inversion of the traditional heliocentric frame of reference of the physical universe. The universe in this model is regarded as being inside a comparatively huge hollow earth. This is a relativistic thought experiment, no more absurd than showing the world upside-down by another form of inversion of the frame of reference. Frames of reference are not discovered though observation or experimentation but are chosen by human beings for their usefulness, or in my case, their beauty.

I regard reductionism and materialism as useful analytical tools that should not to be taken seriously. The universe to me is a symbolic construction created by human beings who are the most complex phenomena in the universe, and not impotent observers outside it. Materialism is a belief system in which matter is believed to be more real than symbols. This is a useful abstraction, but not to be taken any more seriously. Only by insisting that we could turn the universe inside-out through voting on the Internet could I provoke people into realising that what we call reality is a human artistic construct based on the accumulation of knowledge and its systematisation.

LEAVING THE IVORY TOWER

In 1974 I arrived in Christchurch with thousands of posters with an upside-down world on one side and an inside-out universe on the other and announced my intention to try out an “imagination experiment” to test my cosmology. I was not able to get the necessary support and even thirty-five years of exhibiting myself and my new universe in Cathedral Square, daily during the summer, has so far produced little more than laughter.

The five-yearly census in New Zealand presented a problem in retaining my identity as an artistic creation. In 1980 I succeeded in having my title as Living Work of Art transferred to the city art gallery in Christchurch and in 1982 the NZ Art Gallery Directors Council jointly confirmed my status in New Zealand as The Living work of Art.

I have become a popular figure in New Zealand though I am frequently regarded as dangerous by narrow minded religious, scientific and political fundamentalists who see me as evil, insane, or politically incorrect. So far they have been successful in keeping me out of any mainstream spiritual, intellectual or cultural life but my recent award of the Queen’s Service Medal

for bringing colour and imaginative humour to the people of New Zealand may lead to sufficient recognition of my contribution to artistic creativity to enable me to undertake the major imagination experiment in transforming human consciousness I have been planning since 1973.